1.bourgeois

Bourgeoisie (Eng.: /bʊərʒwɑːˈziː/; French pronunciation: [buʁʒwazi]) is a word from the French language, used in the fields of political economy, political philosophy, sociology, and history, which originally denoted the wealthy stratum of the middle class that originated during the latter part of the Middle Ages (AD 500–1500).[1][2] The utilization and specific application of the word is from the realm of the social sciences. In sociology and in political science, the noun bourgeoisie and the adjective bourgeois are terms that describe a historical range of socio-economic classes. As such, in the Western world, since the late 18th century, the bourgeoisie describes a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital, and their related culture"; hence, the personal terms bourgeois (masculine) and bourgeoise (feminine) culturally identify the man or woman who is a member of the wealthiest social class of a given society, and their materialistic worldview (Weltanschauung). In Marxist philosophy, the term bourgeoisie denotes the social class who owns the means of production and whose societal concerns are the value of property and the preservation of capital, in order to ensure the perpetuation of their economic supremacy in society.[3] Joseph Schumpeter instead saw the creation of new bourgeoisie as the driving force behind the capitalist engine, particularly entrepreneurs who took risks in order to bring innovation to industries and the economy through the process of creative destruction.[4]

Contents

[hide]

Etymology[edit]

The Modern French word bourgeois derived from the Old French burgeis (walled city), which derived from bourg (market town), from the Old Frankish burg (town); in other European languages, the etymologic derivations are the Middle English burgeis, the Middle Dutch burgher, the German Bürger, the Modern English burgess, and the Polish burżuazja, which occasionally is synonymous with the intelligentsia.[5] In English, “bourgeoisie” (a French citizen-class) identified a social class oriented to economic materialism and hedonism, and to upholding the extreme political and economic interests of the capitalist ruling class.[6] In the 18th century, before the French Revolution (1789–99), in the French feudal order, the masculine and feminine terms bourgeois and bourgeoise identified the rich men and women who were members of the urban and rural Third Estate — the common people of the French realm, who violently deposed the absolute monarchy of the Bourbon King Louis XVI (r. 1774–91), his clergy, and his aristocrats. Hence, since the 19th century, the term "bourgeoisie" usually is politically and sociologically synonymous with the ruling upper class of a capitalist society.[7]

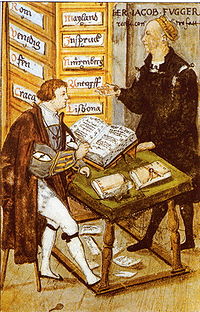

Historically, the medieval French word bourgeois denoted the inhabitants of the bourgs (walled market-towns), the craftsmen, artisans, merchants, and others, who constituted "the bourgeoisie", they were the socio-economic class between the peasants and the landlords, between the workers and the owners of the means of production. As the economic managers of the (raw) materials, the goods, and the services, and thus the capital (money) produced by the feudal economy, the term "bourgeoisie" evolved to also denote the middle class — the businessmen and businesswomen who accumulated, administered, and controlled the capital that made possible the development of the bourgs into cities.[8]

Contemporarily, the terms "bourgeoisie" and "bourgeois" identify the ruling class in capitalist societies, as a social stratum; while "bourgeois" describes the Weltanschauung (worldview) of men and women whose way of thinking is socially and culturally determined by their economic materialism and philistinism, a social identity catalogued and described in drame bourgeois (bourgeois drama), which satirizes buying the trappings of a noble-birth identity as the means climbing the social ladder.[9][10] (See: Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, 1670.)

History[edit]

Origins and rise

In the 11th century, the bourgeoisie emerged as a historical and political phenomenon when the bourgs of Central and Western Europe developed into cities dedicated to commerce. The organised economic concentration that made possible such urban expansion derived from the protective self-organisation into guilds, which became necessary when individual businessmen (craftsmen, artisans, merchants, et alii) conflicted with their rent-seeking feudal landlords who demanded greater-than-agreed rents. In the event, by the end of the Middle Ages (ca. AD 1500), under régimes of the early national monarchies of Western Europe, the bourgeoisie acted in self-interest, and politically supported the king or the queen against the legal and financial disorder caused by the greed of the feudal lords.[citation needed] In the late-16th and early 17th centuries, the bourgeoisies of England and the Netherlands had become the financial — thus political — forces that deposed the feudal order; economic power had vanquished military power in the realm of politics.[8]

From progress to reaction

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the bourgeoisie were the politically progressive social class who supported the principles of constitutional government and of natural right, against the Law of Privilege and the claims of rule by divine right that the nobles and prelates had autonomously exercised during the feudal order. The motivations for the English Civil War (1642–51), the American War of Independence (1775–83), and French Revolution (1789–99) partly derived from the desire of the bourgeoisie to rid themselves of the feudal trammels and royal encroachments upon their personal liberty, commercial rights, and the ownership of property. In the 19th century, the bourgeoisie propounded liberalism, and gained political rights, religious rights, and civil liberties for themselves and the lower social classes; thus was the bourgeoisie then a progressive philosophic and political force in modern Western societies.

By the middle of the 19th century, subsequent to the Industrial Revolution (1750–1850), the great expansion of the bourgeoisie social class caused its self-stratification — by business activity and by economic function — into the haute bourgeoisie (bankers and industrialists) and the petite bourgeoisie (tradesmen and white-collar workers). Moreover, by the end of the 19th century, the capitalists (the original bourgeoisie) had ascended to the upper class, whilst the developments of technology and technical occupations allowed the ascension of working-class men and women to the lower strata of the bourgeoisie; yet the social progress was incidental.

In the event, despite its initial philosophic progressivism — from feudalism to liberalism to capitalism — the bourgeoisie social class (haute and petite) became reactionary in their refusal to allow the ascension (economic, social, political) of people from the proletariat (peasants and urban workers) in order to maintain hegemony.[8]

Denotations[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

The Dictatorship of the Bourgeoisie[edit]

In the Middle Ages (AD 500–1500), the bourgeois usually was a self-employed businessman — such as a merchant, banker, or entrepreneur — whose economic role in society was being the financial intermediary to the feudal landlord and the peasant who worked the fief, the land of the lord. Yet, by the 18th century, the time of the Industrial Revolution (1750–1850) and of industrial capitalism, the bourgeoisie had become the economic ruling class who owned the means of production (capital and land), and who controlled the means of coercion (armed forces and legal system, police forces and prison system). In such a society, the bourgeoisie’s ownership of the means of production enabled their employment and exploitation of the wage-earning working class (urban and rural), people whose sole economic means is labour; and the bourgeois control of the means of coercion suppressed the socio-political challenges of the lower classes, and so preserved the economic status quo; workers remained workers, and employers remained employers.[11]

In the 19th century, the German economist Karl Marx distinguished two types of bourgeois capitalist: (i) the functional capitalist, the business administrator of the means of production; and (ii) the rentier capitalist whose livelihood derives either from the rent of property or from the interest-income produced by finance capital, or both.[12] In the course of economic relations, the working class and the bourgeoisie continually engage in class struggle, wherein the capitalists exploit the workers, whilst the workers resist their economic exploitation, which occurs because the worker owns no means of production, and, to earn a living, he or she seeks employment from the bourgeois capitalist; the worker produces goods and services that are property of the employer, who sells them for a price. The money generated by the sale of the goods and services yields three sums (i) the wages of the worker, (ii) the costs of production, and (iii) profit (surplus value). Thereby, the capitalist profits (makes extra money) by selling the surplus value of the labour of the workers; hence is new wealth created through work.

Besides describing the social class who own the means of production, the Marxist usage of the term "bourgeois" also describes the consumerist style of life derived from the ownership of capital and real property. As an economist Karl Marx acknowledged the bourgeois industriousness that created wealth, yet criticised the moral hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie when they ignored the true origins of their wealth — the exploitation of the proletariat, the urban and rural workers. Further sense denotations of “bourgeois” describe ideologic concepts such as “bourgeois freedom”, which is opposed to substantive forms of freedom; “bourgeois independence”; “bourgeois personal individuality”; the “bourgeois family”; et cetera, all derived from owning capital and property. (See: The Communist Manifesto, 1848.)

Nomenclatura[edit]

In the 20th century, some communist states, particularly the Soviet Union, developed a nomenklatura, constituted by the bureaucrats who administrated the country’s government, industry, agriculture, education, system of state capitalism, et cetera. This New class can be considered a reconstitution of the bourgeoisie within a purportedly socialist state.

In France and French-speaking countries[edit]

In English, the term 'bourgeoisie' is often used to denote the middle classes. In fact, the French term encompasses both the upper and middles classes,[citation needed] a misunderstanding which has occurred in other languages as well. The 'bourgeoisie' consists of four evolving social layers: 'la petite bourgeoisie', 'la moyenne bourgeoisie', 'la grande bourgeoisie', and 'la haute bourgeoisie'.

La Petite Bourgeoisie

The 'petite bourgoisie' consists of people who have experienced a brief ascension in social mobility for one or two generations.[citation needed] It usually starts with a trade or craft, and by the second and third generation, the person may have risen to the ranks of the 'moyenne bourgeoisie'. This class would belong to the British middle middle class and would be part of the American lower middle class. They are distinguished mainly by their mentality, and would differentiate themselves from the proletariat. This class would include artisans, small traders, shopkeepers, and small farm owners. They are not employed, but may not be able to afford employees themselves.

La Moyenne Bourgeoisie

People who belong to the moyenne bourgeoisie have solid incomes and assets, but without the aura of the 'grande bourgeoisie'. They tend to belong to a bourgeois family that has been bourgeois for three or more generations.[citation needed] Some members of this class may have relatives from similar backgrounds, or even have aristocratic connections. The 'moyenne bourgeoisie' would be the equivalent of the British and American upper-middle classes.

La Grande Bourgeoisie

The grande bourgeoisie are families that have been bourgeois since the 19th century, or have been bourgeois for at least four or five generations.[citation needed] Members of these families tend to marry with the aristocracy or make other advantageous marriages (advantageous, like all marriages in all social classes). This bourgeoisie has a large historical and cultural heritage, which has accumulated over the decades. The names of these families are generally known in the city where they reside, and their ancestors have often contributed to the region's history. These families are respected and revered. They belong to the upper class, and in the British class system would qualify as 'gentry'. In the French-speaking countries they are sometimes called 'la petite haute bourgeoisie'.

La Haute Bourgeoisie

The haute bourgeoisie is a social rank in the bourgeoisie that can only be acquired through time. In France, it is composed of bourgeois families that have existed since the French Revolution.[citation needed] They hold only honorable professions and have experienced many illustrious marriages in their family's history. The cultural and historical heritage are large, and their financial means are more than secure. These families exude an aura of nobility, which prevents them from certain marriages or occupations. Due to circumstances, the lack of opportunity, and political regime, they have not been ennobled, and remain simply 'bourgeois'. These people nevertheless live a lavish lifestyle, enjoying the company of the greatest artists of their time. In France, the families of the 'haute bourgeoisie' are referred to as 'les 200 familles', a term which was coined in the first half of the 20th century. Michel Pinçon and Monique Pinçon-Charlot have studied the lifestyle of the French bourgeoisie, and how they boldly guard their world from the 'nouveau riche' or 'new money'.

In the French language, the 'bourgeoisie' is almost designated as a caste by itself, even though social mobility into this socio-economic group is possible. Nevertheless, the French term differentiates itself from 'la classe moyenne', which consists mostly of white-collar employees. This is where further confusion arises, as the English language does not make this separation when referring to the different layers of the middle class. To complicate things further, a 'bourgeois' may appear to have a white-collar job, when in reality they hold a 'profession libérale', which 'la classe moyenne' in its definition is not entitled to.[citation needed] Yet, in English the definition of a white-collar job encompasses the 'profession libérale'. As the world becomes globalized and society moves towards a corporate one, 'la bourgeoisie' in its pure form has become a somewhat outdated term,[citation needed] which requires a more up-to-date definition.

Modern history[edit]

Fascist Italy

Because of their ascribed cultural excellence as a social class, the Italian fascist régime (1922–45) of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini regarded the bourgeoisie as an obstacle to Modernism in aid to transforming Italian society.[13] Nonetheless, despite such intellectual and social hostility, the Fascist State ideologically exploited the Italian bourgeoisie and their materialistic, middle-class spirit, for the more efficient cultural manipulation of the upper (aristocratic) and the lower (working) classes of Italy. In 1938, Prime Minister Mussolini gave a speech wherein he established a clear ideological distinction between capitalism (the social function of the bourgeoisie) and the bourgeoisie (as a social class), whom he dehumanized by reducing them into high-level abstractions: a moral category and a state of mind.[13] Culturally and philosophically, Mussolini isolated the bourgeoisie from Italian society by portraying them as social parasites upon the Fascist Italian State and “The People”; as a social class who drained the human potential of Italian society, in general, and of the working class, in particular; as exploiters who victimized the Italian nation with an approach to life characterised by hedonism and materialism.[13] Nevertheless, despite the slogan The Fascist Man Disdains the ″Comfortable″ Life, which epitomized the anti-bourgeois principle, in its final years of power, for mutual benefit and profit, the Mussolini Fascist régime transcended ideology in order to merge the political and financial interests of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini with the political and financial interests of the bourgeoisie, the Catholic social circles who constituted the ruling class of Italy.

Philosophically, as a materialist creature, the bourgeois man was irreligious; thus, to establish an existential distinction between the supernatural faith of the Roman Catholic Church and the materialist faith of temporal religion; in The Autarchy of Culture: Intellectuals and Fascism in the 1930s, the priest Giuseppe Marino said that:

Christianity is essentially anti-bourgeois . . . A Christian, a true Christian, and thus a Catholic, is the opposite of a bourgeois.[14]

Culturally, the bourgeois man is unmanly, effeminate, and infantile; describing his philistinism in Bonifica antiborghese (1939), Roberto Paravese said that the:

Middle class, middle man, incapable of great virtue or great vice: and there would be nothing wrong with that, if only he would be willing to remain as such; but, when his child-like or feminine tendency to camouflage pushes him to dream of grandeur, honours, and thus riches, which he cannot achieve honestly with his own “second-rate” powers, then the average man compensates with cunning, schemes, and mischief; he kicks out ethics, and becomes a bourgeois.

The bourgeois is the average man who does not accept to remain such, and who, lacking the strength sufficient for the conquest of essential values — those of the spirit — opts for material ones, for appearances.[15]

The economic security, financial freedom, and social mobility of the bourgeoisie threatened the philosophic integrity of Italian Fascism, the ideologic monolith that was the régime of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. Any assumption of legitimate political power (government and rule) by the bourgeoisie represented a Fascist loss of totalitarian State power for social control through political unity — one people, one nation, one leader. Sociologically, to the fascist man, to become a bourgeois was a character flaw inherent to the masculine mystique; therefore, the ideology of Italian Fascism scornfully defined the bourgeois man as “spiritually castrated”.[15]

Bourgeois culture[edit]

Cultural hegemony

Karl Marx said that the culture of a society is dominated by the mores of the ruling-class, wherein their superimposed value system is abided by each social class (the upper, the middle, the lower) regardless of the socio-economic results it yields to them. In that sense, contemporary societies are bourgeois to the degree that they practice the mores of the small-business “shop culture” of early modern France; which the writer Émile Zola (1840–1902) naturalistically presented, analysed, and ridiculed in the twenty-two-novel series (1871–1893) about Les Rougon-Macquart family; the thematic thrust is the necessity for social progress, by subordinating the economic sphere to the social sphere of life.[16]

Conspicuous consumption

The critical analyses of the bourgeois mentality by the German intellectual Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) indicated that the shop culture of the petite bourgeoisie established the sitting room as the centre of personal and family life; as such, the English bourgeois culture is a sitting-room culture of prestige through conspicuous consumption. The material culture of the bourgeoisie concentrated upon mass-produced luxury goods of high quality; generationally, the only variance was the materials with which the goods were manufactured. In the early part of the 19th century, the bourgeois house contained a home that first was stocked and decorated with hand-painted porcelain, machine-printed cotton fabrics, machine-printed wallpaper, and Sheffield steel (crucible and stainless), the utility of which was inherent to its practical functions. Whereas, in the latter part of the 19th century, the bourgeois house contained a home that had been remodelled by conspicuous consumption, whereby the goods were bought to display wealth (discretionary income), rather than for their practical utility. The bourgeoisie had transposed the wares of the shop window to the sitting room, where the clutter of display signalled bourgeois success.[17] (See: Culture and Anarchy, 1869.)

Two spatial constructs manifest the bourgeois mentality: (i) the shop-window display, and (ii) the sitting room. In English, the term “sitting-room culture” is synonymous for “bourgeois mentality”, a philistine cultural perspective from the Victorian Era (1837–1901), especially characterised by the repression of emotion and of sexual desire; and by the construction of a regulated social-space where “propriety” is the key personality trait desired in men and women.[17] Nonetheless, from such a psychologically constricted worldview, regarding the rearing of children, contemporary sociologists claim to have identified “progressive” middle-class values, such as respect for non-conformity, self-direction, autonomy, gender equality and the encouragement of innovation; as in the Victorian Era, the transposition to the U.S. of the bourgeois system of social values has been identified as a requisite for employment success in the professions.[18][19]

Representations

Beyond the intellectual realms of political economy, history, and political science that discuss, describe, and analyse the bourgeoisie as a social class, the colloquial usage of the sociological terms bourgeois and bourgeoise describe the social stereotypes of the Old Money and of the Nouveau riche, who is a politically timid conformist satisfied with a wealthy, consumerist style of life characterised by conspicuous consumption and the continual striving for prestige.[20][21] This being the case, the cultures of the world describe the philistinism of the middle-class personality, produced by the excessively rich life of the bourgeoisie, is examined and analysed in comedic and dramatic plays, novels, and films. (See: Authenticity.)

Theatre

Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (The Would-be Gentleman, 1670) by Molière (Jean-Baptiste Poquelin), is a comedy-ballet that satirizes Monsieur Jourdain, the prototypical nouveau riche man who buys his way up the social-class scale, in order to realise his aspirations of becoming a gentleman, to which end he studies dancing, fencing, and philosophy, the trappings and accomplishments of a gentleman, in order to be able to pose as a man of noble birth, someone who, in 17th-century France, was a man to the manor born; Jourdain’s self-transformation also requires managing the private life of his daughter, so that her marriage can also assist his social ascent.[10][22]

Literature

Buddenbrooks (1901), by Thomas Mann (1875–1955), chronicles the moral, intellectual, and physical decay of a rich family through its declines, material and spiritual, in the course of four generations, beginning with the patriarch Johann Buddenbrook Sr. and his son, Johann Buddenbrook Jr., who are typically successful German businessmen; each is a reasonable man of solid character. Yet, in the children of Buddenbrook Jr., the materially comfortable style of life provided by the dedication to solid, middle-class values elicits decadence: The fickle daughter, Toni, lacks and does not seek a purpose in life; son Christian is honestly decadent, and lives the life of a ne’er-do-well; and the businessman son, Thomas, who assumes command of the Buddenbrook family fortune, occasionally falters from middle-class solidity by being interested in art and philosophy, the impractical life of the mind, which, to the bourgeoisie, is the epitome of social, moral, and material decadence.[23][24][25]

Babbitt (1922), by Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951), satirizes the American bourgeois George Follansbee Babbitt, a middle-aged realtor, booster, and joiner in the Midwestern city of Zenith, who — despite being unimaginative, self-important, and hopelessly conformist and middle-class — is aware that there must be more to life than money and the consumption of the best things that money can buy. Nevertheless, he fears being excluded from the mainstream of society more than he does living for himself, by being true to himself — his heart-felt flirtations with independence (dabbling in liberal politics and a love affair with a pretty widow) come to naught because he is existentially afraid.

Yet, George F. Babbitt sublimates his desire for self-respect, and encourages his son to rebel against the conformity that results from bourgeois prosperity, by recommending that he be true to himself:

2.Proletariat

As defined in the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the proletarii constituted a social class of Roman citizens owning little or no property.

The origin of the name is presumably linked with the census, which Roman authorities conducted every five years to produce a register of citizens and their property from which their military duties and voting privileges could be determined. For citizens with property valued 11,000 asses or less, which was below the lowest census for military service, their children—proles (from Latin proli, "offspring")—were listed instead of their property; hence, the name proletarius, "the one who produces offspring". The only contribution of a proletarius to the Roman society was seen in his ability to raise children, the future Roman citizens who can colonize new territories conquered by the Roman Republic and later by the Roman Empire. The citizens who had no property of significance were called capite censi because they were "persons registered not as to their property...but simply as to their existence as living individuals, primarily as heads (caput) of a family."[2][3]

Although included in one of the five support centuriae of the Comitia Centuriata, proletarii were largely deprived of their voting rights due to their low social status caused by their lack of "even the minimum property required for the lowest class"[4] and a class-based hierarchy of the Comitia Centuriata. The late Roman historians, such as Livy, not without some uncertainty, understood the Comitia Centuriata to be one of three forms of popular assembly of early Rome composed of centuriae, the voting units whose members represented a class of citizens according to the value of their property. This assembly, which usually met on the Campus Martius to discuss public policy issues, was also used as a means of designating military duties demanded of Roman citizens.[5] one of reconstructions of the Comitia Centuriata features 18 centuriae of cavalry, and 170 centuriae of infantry divided into five classes by wealth, plus 5 centuriae of support personnel called adsidui. The top infantry class assembled with full arms and armor; the next two classes brought arms and armor, but less and lesser; the fourth class only spears; the fifth slings. In voting, the cavalry and top infantry class were enough to decide an issue; as voting started at the top, an issue might be decided before the lower classes voted.[6] In the last centuries of the Roman Republic (509-44 B.C.), the Comitia Centuriata became impotent as a political body, which further eroded already minuscule political power the proletarii might have had in the Roman society.

Following a series of wars the Roman Republic engaged since the closing of the Second Punic War (218–201), such as the Jugurthine War and conflicts in Macedonia and Asia, the significant reduction in the number of Roman family farmers had resulted in the shortage of people whose property qualified them to perform the citizenry's military duty to Rome.[7] As a result of the Marian reforms initiated in 107 B.C. by the Roman general Gaius Marius (157–86), the proletarii became the backbone of the Roman Army.[8]

Karl Marx, who studied Roman law at the University of Berlin,[9] used the term proletariat in his socio-political theory of Marxism to describe a working class unadulterated by private property and capable of a revolutionary action to topple capitalism in order to create classless society.

Usage in Marxist theory[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

The term proletariat is used in Marxist theory to name the social class that does not have ownership of the means of production and whose only means of subsistence is to sell their labour power[10] for a wage or salary. Proletarians are wage-workers, while some refer to those who receive salaries as the salariat. For Marx, however, wage labor may involve getting a salary rather than a wage per se. Marxism sees the proletariat and bourgeoisie (capitalist class) as occupying conflicting positions, since workers automatically wish their wages to be as high as possible, while owners and their proxies wish for wages (costs) to be as low as possible.

In Marxist theory, the borders between the proletariat and some layers of the petite bourgeoisie, who rely primarily but not exclusively on self-employment at an income no different from an ordinary wage or below it – and the lumpen proletariat, who are not in legal employment – are not necessarily well defined. Intermediate positions are possible, where some wage-labour for an employer combines with self-employment. While the class to which each individual person belongs is often hard to determine, from the standpoint of society as a whole, taken in its movement (i.e. history), the class divisions are incontestable; the easiest proof of their existence is the class struggle – strikes, for instance. While an employee may be subjectively unsure of his class belonging, when his workmates come out on strike he is objectively forced to follow one class (his workmates, i.e. the proletariat) over the other (management, i.e. the bourgeoisie). Marx makes a clear distinction between proletariat as salaried workers, which he sees a progressive class, and Lumpenproletariat, "rag-proletariat", the poorest and outcasts of the society, such as beggars, tricksters, entertainers, buskers, criminals and prostitutes, which he considers a retrograde class.[11][12] Socialist parties have often struggled over the question of whether they should seek to organize and represent all the lower classes, or just the wage-earning proletariat.

According to Marxism, capitalism is a system based on the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie. This exploitation takes place as follows: the workers, who own no means of production of their own, must use the means of production that are property of others in order to produce, and, consequently, earn their living. Instead of hiring those means of production, they themselves get hired by capitalists and work for them, producing goods or services. These goods or services become the property of the capitalist, who sells them at the market.

One part of the wealth produced is used to pay the workers' wages (variable costs), another part to renew the means of production (constant costs) while the third part, surplus value is split between the capitalist's private takings (profit), and the money used to pay rents, taxes, interests, etc. Surplus value is the difference between the wealth that the proletariat produces through its work, and the wealth it consumes to survive and to provide labor to the capitalist companies.[13] A part of the surplus value is used to renew or increase the means of production, either in quantity or quality (i.e., it is turned into capital), and is called capitalised surplus value.[14] What remains is consumed by the capitalist class.

The commodities that proletarians produce and capitalists sell are valued for the amount of labor embodied in them. The same goes for the workers' labor power itself: it is valued, not for the amount of wealth it produces, but for the amount of labor necessary to produce and reproduce it. Thus the capitalists earn wealth from the labor of their employees, not as a function of their personal contribution to the productive process, which may even be null, but as a function of the juridical relation of property to the means of production. Marxists argue that new wealth is created through labor applied to natural resources.[15]

Marx argued that it was the goal of the proletariat to displace the capitalist system with the dictatorship of the proletariat, abolishing the social relationships underpinning the class system and then developing into a communist society in which "the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all".[16]

See also[edit]

Reference notes[edit]

- Jump up ^ proletariat. Accessed: 6 June 2013.

- Jump up ^ Adolf Berger, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society 1953) at 380; 657.

- Jump up ^ Arnold J. Toynbee, especially in his A Study of History, uses the word Proletariat in this general sense of people without property or a stake in society. Toynbee focuses particularly on the generative spiritual life of the "internal proletariat" (those living within a given civil society). He also describes the "heroic" folk legends of the "external proletariat" (poorer groups living outside the borders of a civilization). Cf., Toynbee, A Study of History (Oxford University 1934–1961), 12 volumes, in Volume V Disintegration of Civilizations, part one (1939) at 58–194 (internal proletariat), and at 194–337 (external proletariat).

- Jump up ^ Berger, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (1953) at 351; 657 (quote).

- Jump up ^ Titus Livius (c.59 BC-AD 17), Ab urbe condita, 1, 43; the first five books translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt as Livy, The Early History of Rome (Penguin 1960, 1971) at 81–82.

- Jump up ^ Andrew Lintott, The Constitution of the Roman Republic (Oxford University 1999) at 55–61, re the Comitia Centuriata.

- Jump up ^ Cf., Theodor Mommsen, Römisches Geschichte (1854–1856), 3 volumes; translated as History of Rome (1862–1866), 4 volumes; reprint (The Free Press 1957) at vol.III: 48–55 (Mommsen's Bk.III, ch.XI toward end).

- Jump up ^ H. H. Scullard, Gracchi to Nero. A History of Rome from 133 BC to AD 68 (London: Methuen 1959, 4th ed. 1976) at 51–52.

- Jump up ^ Cf., Sidney Hook, Marx and the Marxists (Princeton: Van Nostrand 1955) at 13.

- Jump up ^ Marx, Karl (1887). "Chapter Six: The Buying and Selling of Labour-Power" (html). In Frederick Engels. Das Kapital, Kritik der politischen Ökonomie [Capital: Critique of Political Economy]. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Jump up ^ Lumpen proletariat – Britannica online Encyclopedia

- Jump up ^ Marx, Karl (February 1848). "Bourgeois and Proletarians". Manifesto of the Communist Party. Progress Publishers. Retrieved 10 February 2013. Cite uses deprecated parameters (help)

- Jump up ^ Marx, Karl. The Capital, volume 1, chapter 6. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch06.htm

- Jump up ^ Luxemburg, Rosa. The Accumulation of Capital. Chapter 6, Enlarged Reproduction, http://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1913/accumulation-capital/ch06.htm

- Jump up ^ Marx, Karl. Critique of the Gotha Programme, I. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/ch01.htm

- Jump up ^ Marx, Karl. The Communist Manifesto, part II, Proletarians and Communists http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm

'其他 > 成语集' 카테고리의 다른 글

| McCarthyism (0) | 2014.04.15 |

|---|---|

| 自己身正不怕影斜 (0) | 2014.03.18 |

| 霜固帶 (0) | 2014.03.08 |

| 不在其位 不謀其政 (0) | 2014.03.08 |

| 재선충(材線蟲)-한글 교육의 병폐 -국어 망조(亡兆) (0) | 2014.03.03 |